Unfinished Business

12 October 2023

ShareUnfinished works of art, far from being of minor significance, can be of exceptional interest and value.

Colin Gleadell

Colin Gleadell writes on the art market for The Daily Telegraph, Artnet and Art Monthly.

Several volumes could be written about unfinished works by artists, why they were left unfinished and how much that may have affected their value. A good exhibition on the subject, ‘Unfinished; Thoughts left Visible’, was staged by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2016 citing nearly 200 examples ranging from a Salvator Mundi by Durer the execution of which had been interrupted by his travels, never to be completed, to a handful of Cézannes and contemporaries such as Louise Bourgeois. The exhibition was useful in that it went some way into dissecting the meaning of ‘unfinished’ and whether it was unintentional as in Lucian Freud’s last, uncompleted painting, intentional, or ‘non finito’, as in many cases by Titian, or just a sketch, as in Manet’s The Funeral which was described by Camille Pissarro, who bought it, as ‘an extraordinary sketch.’ A portrait which Alice Neel could not finish when the sitter stopped modelling for her looks clearly unfinished but is signed on the back signalling that the artist was happy to call it complete. And the fact that ’Unfinished’ was staged in a museum underlined how an unfinished work, far from being of minor significance, could be of exceptional interest and value. Titus Kaphar, ‘Page 4 of Jefferson’s “Farm Book”’, signed and dated 18 on the reverse, oil and tar on linen mounted on panel, 152.4 x 121.9 cm. Sold for $854,900 at Sotheby’s New York in October 2020. Credit: Sotheby’s.

Titus Kaphar, ‘Page 4 of Jefferson’s “Farm Book”’, signed and dated 18 on the reverse, oil and tar on linen mounted on panel, 152.4 x 121.9 cm. Sold for $854,900 at Sotheby’s New York in October 2020. Credit: Sotheby’s.As Degas said of one of his paintings that he never stopped reworking, now in the Mellon collection: "It is one of those works which are sold after a man’s death, and artists buy them not caring whether they are finished or not." Or they could have an appeal outside their own period. An unfinished portrait of a Spanish noblewoman, but with her face blanked out by the 18th German artist Anton Raphael Mengs was estimated at £12,000 at Christie’s in 2012, far below complete portraits by Mengs that can fetch six figures and in line with works by his followers. But it was bought for £40,000 by the dealer, Otto Naumann, for a client.

A good reason for the added value could be the modern, surreal look of the painting, or even the contemporary touch. Titus Kaphar who shows with the Gagosian gallery, blacks out faces and cuts out figures from classical art historical subjects to reconfigure appropriate meaning in our post slavery but still racially tense era. While they make look unfinished, they are absolutely preconceived and they sell for as much as $5 million.

On the other hand, what appears to be the finished version of the Mengs portrait turned up at the Dorotheum in 2020 and sold for €45,300 – little different from the unfinished version.

Anton Raphael Mengs, ‘Portrait of Mariana de Silva y Sarmiento, duquesa de Huescar (1740-1784)’. Sold for £40,000 at Christie’s London in July 2012.

Anton Raphael Mengs, ‘Portrait of Mariana de Silva y Sarmiento, duquesa de Huescar (1740-1784)’. Sold for £40,000 at Christie’s London in July 2012.Image courtesy of: Private Collection, New York.

Anton Raphael Mengs, ‘Portrait of Mariana del Pilar Ana Silva-Bazán y Sarmiento (1739–1784), half-length, with a dog’, oil on canvas, 51 x 41 cm, framed. Sold for €45,300 at the Dorotheum in November 2020. Credit: Dorotheum.

One of the first articles I wrote as art sales correspondent for The Daily Telegraph was in 1998 concerning a painting by Piet Mondrian which he left unfinished at the time of his death. There was enough of the diamond shaped Victory Boogie Woogie, however, to sell to top US collectors, the Tremaines, soon after the artist’s death in 1944 for $8,000 and thence to publisher Si Newhouse in 1987 for $11 million. In 1998, Newhouse was approached by a Dutch art foundation to sell it to them for $40 million so they could donate it to the Gemeentemuseum (now Kunstmuseum) in the Hague....which they did.

Not everyone was overjoyed. Dr Bob van den Boogert of the Rembrandt House Museum expected some skulduggery and complained that, apart from not liking it, “it is an unfinished painting. On the free market it would never have made such a price. We could have acquired at least two good Rembrandts for that price.” However, Joop Joosten, author of the Mondrian catalogue raisonné argued that because it was unfinished it captured unintentionally his working methods as he moved toward a new stage in his development – one that remained tantalisingly undeveloped. And so the price, a record for the artist at the time, was paid.

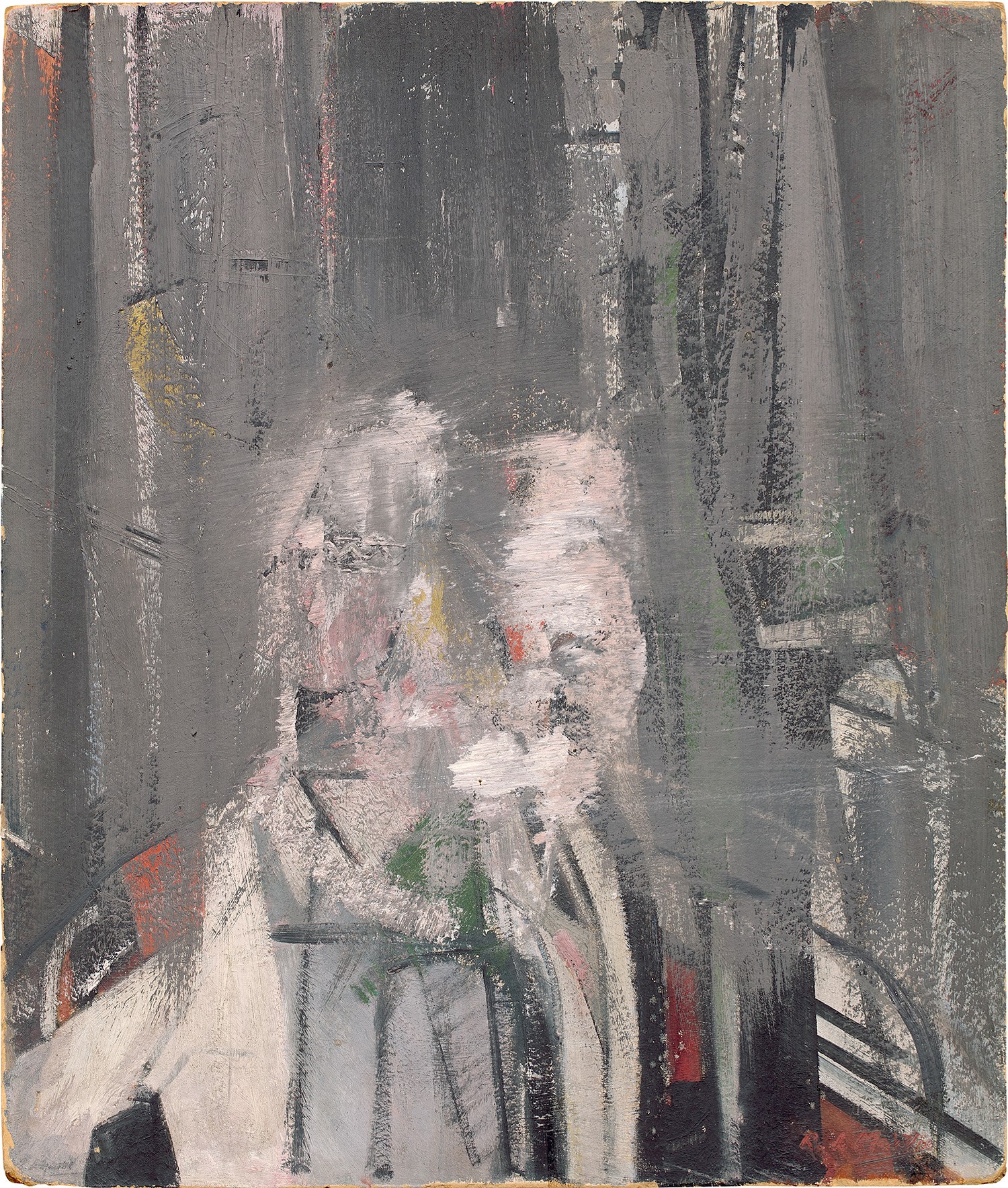

Among the most famous ‘unfinished’ works of the 20th century are the so-called ‘abandoned’ paintings of Francis Bacon. In 1964, Ronald Alley, a curator at the Tate Gallery, published a catalogue raisonné of Bacon’s work to date. In a separate section at the back was a list of abandoned paintings which Bacon did not like or had not finished or had left to artists and friends to paint on the back. For several decades, the abandoned paintings would not be given a full catalogue status in the market so had little value. But after Bacon died in 1992, his estate set about updating the catalogue raisonné to include abandoned paintings with recognised finished works thus enhancing their value.

Several were launched onto the market for the estate by the New York dealer, Tony Shafrazi, cleaned up or ‘enhanced’ as a rival dealer put it to me, with million-dollar price tags.

Francis Bacon, ‘Head’, oil on canvas, 1949. Provenance Robert Buhler, sold for £468,500 at Sotheby’s London in 2008, later sold for £772,000 at Phillips London in March 2022. Copyright: Phillips.

It took 10 years to update this catalogue (2006 -2016) and from the outset the word quickly went round the trade that the abandoned paintings were going to be given added value by inclusion in the new publication. These included several paintings Bacon left behind in his South Kensington flat in 1950 to the painter Robert Buhler. Some of Buhler’s Bacons had been included in Alley’s ‘Abandoned’ paintings catalogue and were considered worthless until word got out that their status was to be revised. By 2008, at the height of an art market boom and 8 years before publication, one of Buhler’s inherited works was sold for £470,000. In 2012, another Buhler Bacon ‘Head’, listed in Alley as ‘Abandoned’ sold at Sotheby’s for close to £1 million and then again at Sotheby’s in Paris in 2019 for €1.7 million. For comparison, a completed Bacon study for a screaming head from 1952 sold in 2019 for $50 million.

Of course, when it comes to financial worth, anything that can be verifiably linked to a famous artist’s hand accrues some value. The case of the slashed and cut out canvases which Bacon put in a refuse bag, but which were recovered by his electrician, surfaced when, many years later, the electrician placed the dismembered shreds, mostly heads with the faces cut out, in Ewbank’s auctions in Surrey. Purist Bacon scholars and dealers pooh-pooh’d the sale as rubbish, but it was a runaway success. One almost complete, if dishevelled portrait sold for £400,000, and group of faceless heads sold for round £40,000 each, some to reputable collections such as jeweller Laurence Graff, who is said to have framed them three in a row like ghostly triptychs.

In a conversation with Tate curator, Jennifer Munday, Bacon said he found it difficult to ‘finish’ a work, and “his canvases often became so clogged with pigment that they had to be discarded.” But nevertheless, he told her he thought his destroyed works were among his best.