Once Banned, Now Prized

19 October 2023

ShareEarly editions of James Joyce's Ulysses are notoriously full of errors but that's what makes them special.

Francesca PeacockFrancesca Peacock is an art, books and culture writer.

When you think of Ulysses, what is it you picture: pasty-faced students, lost in the labyrinthine world of their essays and Dublin’s streets? Or perhaps one of its more glamourous readers: Marilyn Monroe with the book in the playground, her copy tellingly open at the last few pages of Molly Bloom’s famous “yes I said yes I will Yes” monologue?

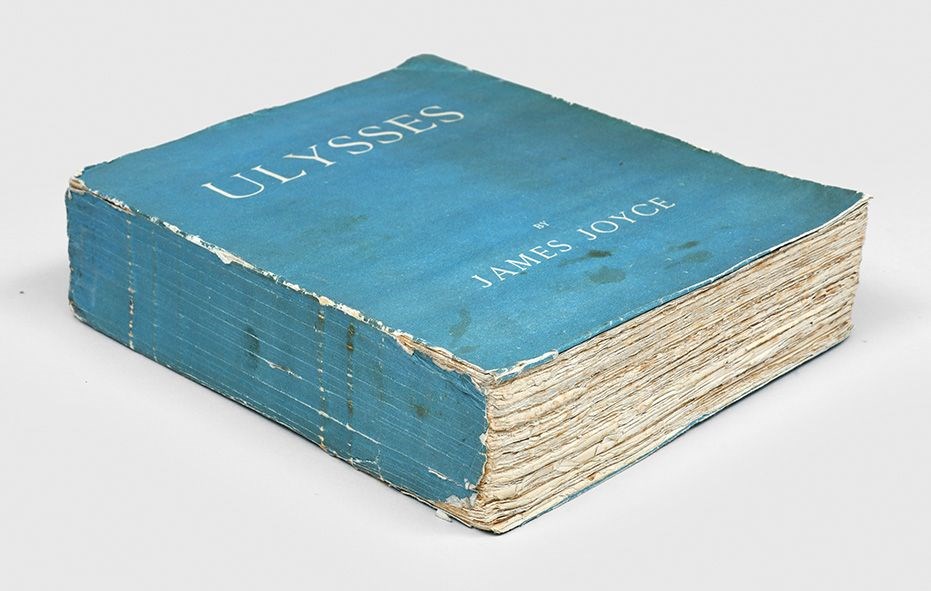

Maybe what sticks in your mind is that illusive, perfect shade of Ulysses blue used in the first edition — a colour Joyce was so particular about that he had it custom-mixed by his artist friend Myron Nutting. It is thought that Joyce was aiming for a “Greek” blue — the colour of the country’s flag, but others have seen it as a “homage to glaucoma” and Joyce’s life-long eye problems. If that sounds like an oblique connection too far, you must remember that this is Ulysses we are dealing with: the book Joyce himself claimed he “put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries”. The first edition is immortalised in a painting by Paul Cadmus: painted in 1931, Cadmus’s nude lover Jarred French looks out of the canvas with a first edition of Ulysses resting on his torso.

open_T638333075333490808.jpg)

Ulysses, James Joyce. Edition: Paris - Shakespeare and Company, 1922. This copy was once on offer for £300,000.

Images courtesy of Peter Harrington.

First published a century ago, Ulysses’ publication history is anything but simple. It was the victim of an obscenity trial in the United States before it was even published as a result of the “Nausicaa” episode appearing in The Little White Review. In the offending scene, Leopold Bloom masturbates on a beach, and ponders tactics for seducing girls: “Nausicaa” is, admittedly, hardly something you’d recommend as a story for a class of four-year-olds. But in the grand scheme of Ulysses (magical sex-shifting prostitutes; orgasmic monologues; lecherous men stalking women around the city), it’s a bit like banning Dad’s Army for bad war jokes before Germany’s even been mentioned for the first time. Ulysses couldn’t legally be published in the US until 1933 after another trial: United States vs. One Book Called Ulysses. Random House, under the leadership of Bennett Cerf, produced an error-laden edition in 1934.

Over in Europe, Sylvia Beach owner of the famous Parisian left-bank bookshop Shakespeare and Company, published 1000 copies with the famous blue cover. Chris Saunders, of the antiquarian bookshop Sotheran’s, pays homage to Beach’s “bravery and nous to publish a book that no one else would touch”. Of all Joyce’s works, Ulysses is this most collectible — and this edition more than any other. Of the first Paris edition, 100 copies were signed, and on Dutch handmade paper, 150 were numbered and printed on verge d’Arches paper (an expensive, watercolourist’s paper), and 750 were printed on bog standard handmade paper.

Ulysses, James Joyce. Edition: Paris - Shakespeare and Company, 1922. One of the copies distributed by Harriet Shaw Weaver.

Image courtesy of Peter Harrington.

One of the 100 copies printed on Dutch paper, in excellent condition was for sale at the London bookshop Peter Harrington for a cool £300,000, a lesser condition copy of the same is currently offered for £55,000. One of the 750 printed on the least special paper — but still in the first 1000 — can set you back over £60,000. Saunders remembers Sotheran’s selling one of the 750 of the first edition for £40,000 in recent years, but he draws attention to the “notoriously fragile” nature of the books — their much-prized blue cover is surprisingly flimsy. He says, “if you have a copy, get a box made for it!”

Just a few months later in 1922, The Egoist Press — under Harriet Shaw Weaver, whose magazine The Egoist had published some episodes as early as 1919 — published 2000 numbered copies of “the English edition” on handmade paper, using the same plates as the first edition. This edition included the first printed list of “errata” — something that would continue to dog Ulysses editions, and debates, for decades to come.

How can you tell what’s an error in Ulysses, and what is just authorial choice? Is a moment of punctuation in an otherwise punctuation-averse scene a strong authorial choice, or a grave printing error that ruins the episode’s meaning? One Joyce scholar, Jack Dalton, went as far as to claim that there were no fewer than 2000 errors in the first printed edition, whilst John Kidd — something of a maverick Joyce scholar — attacked Walter Gabler’s 1984 “corrected text“ as being “marbled with the fat of pseudo-restorations”. In response to what some of us may perceive as a minor errors (“beard” for “bread” and suchlike), Kidd responded — in The New York Review of Books, no less — “is no one awake at the wheel?”

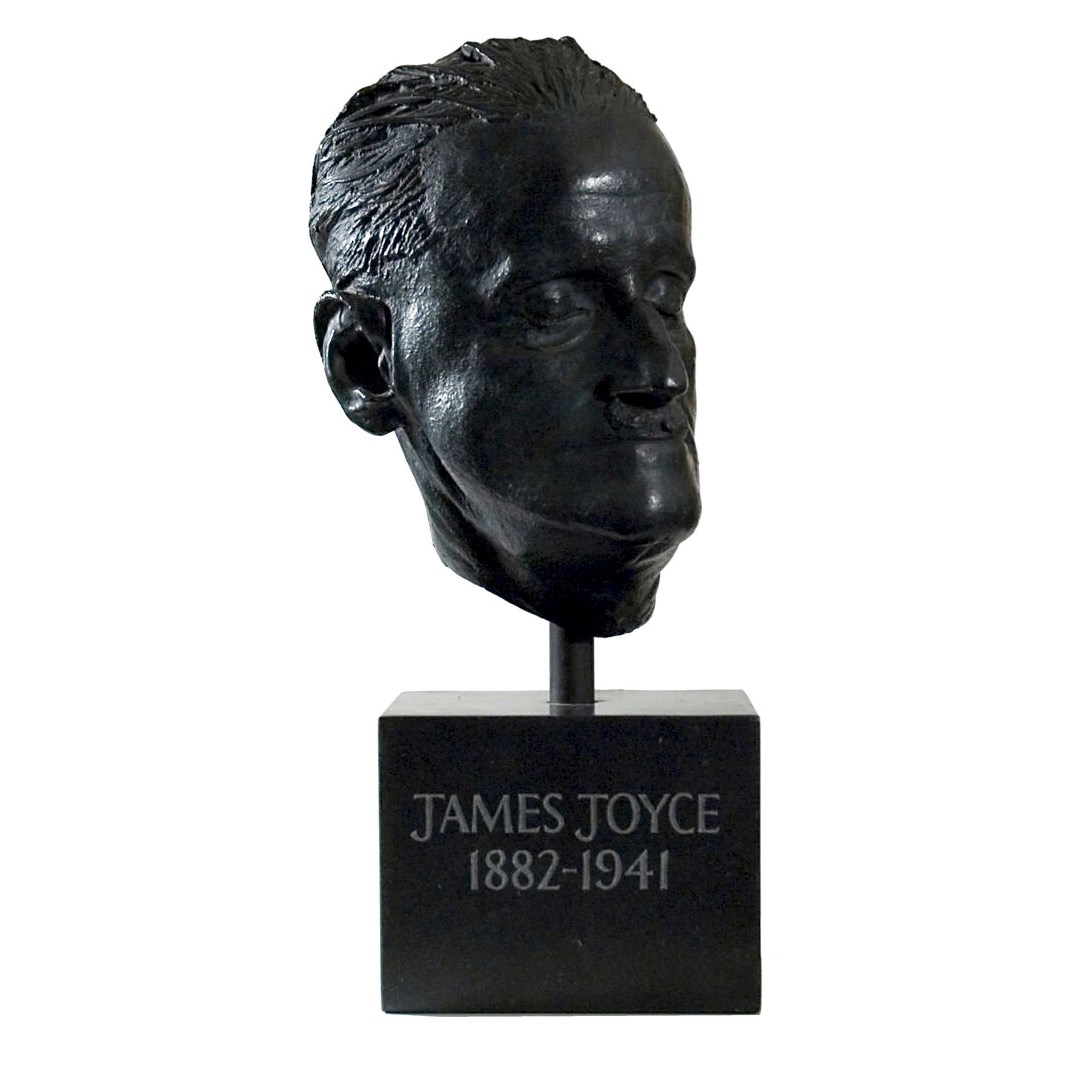

Bronze of James Joyce’s death mask. Cast at Lunt’s Foundry Birmingham, 2017.

Bronze of James Joyce’s death mask. Cast at Lunt’s Foundry Birmingham, 2017.For sale at Sotheran’s. Image courtesy of Henry Sotheran’s Antiquarian Bookdealers.

There is, then, a certain irony to the fact that it is the most error-laden editions of Joyce that are now most prized by collectors: it isn’t the 1932 Odyssey Press edition — “specially revised, at the author’s request” — which, in 2009, sold at a record-breaking price. Indeed, you can buy each of the 1932 volumes for a mere £35 a piece. Blue covers they may lack, but they also have a corresponding absence of printing errors.

It is not just Ulysses which sells for brilliantly high prices: you can buy a bronze cast of Joyce’s death-mask for £4,300, whilst a manuscript notebook of the “Eumaeus” episode reached £861,250 in 2001, and something as seemingly slight — but highly erotic — as a letter between Joyce and his wife Nora went for £240,800 in 2004. If the irony of the error-laden copies reaching hundreds of thousands wasn’t enough, there’s an especial tragedy to the fact that the letter in question was written after the couple had quarrelled over a lack of money.

What would Joyce say if he could see the price his works raised today? Would he be uncharacteristically squeamish, or would he have the commercial mind of Ulysses’s advertising salesman Leopold Bloom. I think the answer might be the latter: “…yes I said yes I will Yes.”

This was first published in The Open Art Fair Magazine.